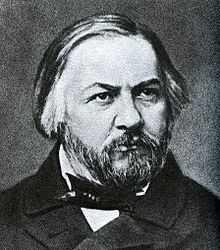

Mikhail Glinka is considered the fountainhead  of Russian classical music, and the first Russian composer to gain widespread recognition in his own country. As a child, he was raised by his over-protective grandmother and was confined to her room, and therefore developed a sickly disposition. The only music he heard during his confinement was the sound of strident church bells and improvisatory peasant choirs. Both of these used unconventional harmonies, which later helped Glinka to break free from the Western tradition of consonant harmony.

of Russian classical music, and the first Russian composer to gain widespread recognition in his own country. As a child, he was raised by his over-protective grandmother and was confined to her room, and therefore developed a sickly disposition. The only music he heard during his confinement was the sound of strident church bells and improvisatory peasant choirs. Both of these used unconventional harmonies, which later helped Glinka to break free from the Western tradition of consonant harmony.

After his grandmother’s death, he moved to live with his uncle, where he heard his uncle’s orchestra perform music by the greats, such as Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. He began violin and piano lessons, and soon began composing as well. He later traveled to Italy to continue his studies, but realized that he wanted to return to Russia and revolutionize Russian music.

Upon returning to Russia, he composed his first two operas, A Life for the Tsar and Ruslan and Lyudmila. However, the latter did not receive much acclaim, which disgruntled Glinka and caused him to move to Paris. From there he moved to Spain, back to Paris, and ultimately back home to Russia once again. His music, particularly Ruslan and Lyudmila, provided a strong foundation for many Russian composers that came after him, such as Alexander Borodin, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

In 1825, Glinka began writing a viola sonata. It was still relatively early in his career, so his music had not yet reached his unique level of complexity, but the first movement of the sonata contains a rich melodiousness that can only be his own. This work was considered by his peers to be a major breakthrough piece from him, a signal of transition from his early, academic pieces to his unique Russian masterpieces. A few years later, he wrote the sonata’s second movement: a larghetto movement B-flat major, a nice contrast to the d minor allegro that was the first movement. He began a third movement in rondo form, typical of many classical sonatas, but never finished it. As a result, only the first two movements of the sonata are ever performed.

Leave a comment